I read this recently in a powerpoint that came with a research methods textbook

If answering the study question adequately requires the use of elaborate analytic techniques, invite a statistical expert to serve as a collaborator and as a coauthor on the resulting paper.

I was so non-plussed that I looked up the word non-plussed in the Merriam-Webster dictionary

a state of bafflement or perplexity … to be at a loss as to what to say, think, or do

Um, this is a research methods COURSE, for graduate students, no less, and your advice to them in doing their research is that if it gets too hard they should find someone else to do it for them? This is not limited to one text or one school, either. At two universities where I have worked, both of which are well-respected and grant doctoral degrees, doctoral students, and post-doctoral students are asked before beginning their research,

Do you have a statistician?

In teaching statistics, I have been asked by doctoral students from multiple disciplines,

Why are we learning this when we are just going to have a statistician do it for us?

Obviously, research no longer means what I thought it meant. I thought that the process of research was that you formulated a question that interested you, you read the scientific literature on that question, generated a hypothesis, collected data from a sample, analyzed that data, evaluated your results and wrote a conclusion. Now, not only is it acceptable, but encouraged to have someone else analyze your data and tell you what it means. I find that perplexing.

This is not how it was when I was in graduate school. Back then, data were analyzed using computer software that ran on mainframe computers, or sometimes mini-computers. A mini-computer was not like an iPad mini. It was taller than me. Some of our data came on tapes which we had to walk across campus and load on to the tape drives ourselves, as we were lowly graduate students and it was assumed we had nothing better to do with our time. Fortunately, I was at the University of California by then and no longer at the University of Minnesota, where crossing campus could require skis. I did some consulting writing code for the data analysis for my fellow students, enough that caused the dean to call me into his office and ask me what I was doing and give me strict instructions, along the lines of

This is not how it was when I was in graduate school. Back then, data were analyzed using computer software that ran on mainframe computers, or sometimes mini-computers. A mini-computer was not like an iPad mini. It was taller than me. Some of our data came on tapes which we had to walk across campus and load on to the tape drives ourselves, as we were lowly graduate students and it was assumed we had nothing better to do with our time. Fortunately, I was at the University of California by then and no longer at the University of Minnesota, where crossing campus could require skis. I did some consulting writing code for the data analysis for my fellow students, enough that caused the dean to call me into his office and ask me what I was doing and give me strict instructions, along the lines of

You can write their programs for them, since this is not a computer science Ph.D., but that is all. You are not to comment or assist in any way with research design, writing their data collection instruments, choosing what analysis to do nor interpreting that analysis. When a person receives a Ph.D. from this university it is supposed to mean that they know how to conduct research, not that they know where to find someone to pay to do their research for them.

It seems that the tables have turned quite a bit. Even my least quantitatively oriented classmate back in the 1980s was probably equivalent to the average “statistical consultant” today. That is, they passed at least four graduate level statistics courses that required both a paper and a final exam with questions like, “How is Analysis of Variance related to stepwise discriminant function analysis?” This was true whether your Ph.D. was in education, business or psychology, because it was assumed, for example, that if you were going to place students in special education because they scored two standard deviations below the mean you should have a definite understanding of what a standard deviation was, what a normal distribution was and where two standard deviations fell on that distribution. Furthermore, as a superintendent or other school administrator, it was expected that you could evaluate the research literature (hence being skeptical of stepwise methods of all types).

It seems to me that what is required for a doctoral degree has been significantly watered down.

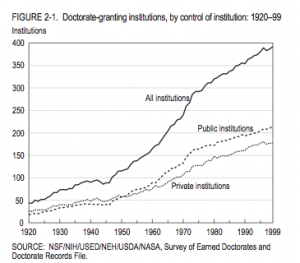

This chart shows the growth in doctorate granting institutions from 1920-99. The trend has continued. When I entered graduate school for my Ph.D. in 1985, there were 337 doctorate-granting institutions in the country. Now there are 418 – a growth of 24% over the past 29 years, on top of what had been, as you can see from the chart, a pretty steep growth rate for the 25 years or so prior to that time.

This chart shows the growth in doctorate granting institutions from 1920-99. The trend has continued. When I entered graduate school for my Ph.D. in 1985, there were 337 doctorate-granting institutions in the country. Now there are 418 – a growth of 24% over the past 29 years, on top of what had been, as you can see from the chart, a pretty steep growth rate for the 25 years or so prior to that time.

Who is teaching all of these new doctoral students? Well, in many instances, it is a horde of very part-time adjuncts. I don’t think adjuncts are necessarily poor teachers – in fact, I make it a point to teach at least one course a year myself – but I am aware of doctoral programs that are run with only ONE full-time faculty member. Given the paucity of human resources, it is no surprise that there is no one around to individually mentor the students in their research. Now, we are entering an era where those students who are graduating with very little research experience are themselves teaching doctoral students. It is a case of the very near-sighted leading the blind.

All of this is making me wonder where they are going to find those statisticians and how well-trained they are really going to be. I just finished with what will probably be my last student project for the next few years – no reflection on that student, or the other four students I worked with over the past two years, all of whom were a perfect delight – but my schedule is completely booked through October, 2015. Almost all of the really good statisticians I know are in the same boat.

I don’t have an answer to any of this. I am non-plussed.