I know G4C will post a video of the talk, but in the interim, I had a few people ask me about the availability of my presentation before the video is up. Here is the text of my talk that I gave at the 2020 Games for Change Festival (online) on July 15, 2020.

“When you want to build a ship, do not begin by gathering wood, cutting boards, and distributing work, but rather awaken within men the desire for the vast and endless sea.”

I’m CEO and co-founder of 7 Generation Games, but was once a journalist where you’re taught never “begin with a quote.” However, sometimes, someone says something so much better or more eloquently than you ever could – such as the words of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry – who knew not only about cultivating passion, but as one of the most successful children’s book authors of all time, clearly knew a thing or two about engaging a youth audience.

Yet, when we talk about how to engage youth, especially those from under-represented backgrounds, in gaming – or any aspect of technology – the conversations go straight to “Let’s teach them to code.”

That’s not to say that there’s not a need for programmers, but why do we always lead with that? I suppose because developer is both a good paying and frequently in-demand position. Of course, to draw from Saint-Exupéry one more time, too often adults conflate money with all things. As he wrote in the Little Prince, “If you tell grown-ups, I saw a beautiful red brick house with geraniums at the windows and doves on the roof…” they won’t be able to imagine such a house. You have to tell them, “I saw a house worth a hundred thousand francs.” Then they exclaim, “What a pretty house!”

Now don’t get me wrong, I have to make payroll every two weeks and am always on the lookout for good programmers, but when I think about the vast majority of people I know in this field, they entered into it, not because they wanted to spend their lives sitting in front of a computer squinting at lines of code with occasional perplexed looks, swear words and fist pumps when something finally runs as expected.

Instead, they’re driven by a desire to create something incredible…

Do you ever think for a second what game design enables us to do? To take something that only existed in the imagination and make it into something people can play. When asked about my favorite part of my job, that’s it.

When I work with kids – which we’ve been able to do from all over the world at this point – that idea and excitement is what I try to impart. Driven to not only create games more reflective of all learners but actively working with youth from marginalized communities around game design as we seek to not only help develop future game designers, but kids who can truly see all they might be able to do in the future.

Underserved or under-represented – are broad terms often used to dance around saying Black, Latino, Indigenous – all of which apply, but it’s also kids who come from economically disadvantaged areas, from rural communities to the inner city – and outside of the United States, it’s anywhere kids are playing games and consuming content developed elsewhere and completely unrepresentative of anything relating to their daily life.

When you think about it, the VAST majority of kids do not see themselves in the games they play, the media they consume or the curriculum they’re taught.

Games, especially educational games, provide an opportunity to work toward changing that. I am under no illusions that 7 Generation Games is going to single-handedly remedy any of the vast challenges faced in education. But if you are developing learning games and not trying to be part of the solution, you’re contributing to the problem.

Now this talk is about empowering underserved youth through game design. If you are hoping for a quick model to drop into economically disadvantaged communities, do a game design workshop for a few hours and then leave, job done, my apologies.

Engaging and empowering kids through design — or anything else for that matter — is important and rewarding but not the kind of thing where you can just parachute in for an afternoon.

“I want you to come do that game design thing with our kids,” a program director at a school on the Standing Rock Reservation said when she called me. “But you have to promise that you’ll keep coming back. Our kids have had too many people drop in and out of their lives. They have too many people expect them to amount to nothing. I want them to see they can do anything – but they don’t even know what the possibilities are.”

My mother talks about how when she was young, she had no idea what people who worked in shiny office buildings with lots of windows did. She was a young Latina in the 1960s, when the only way someone like her would be working in one of those buildings was as a secretary or cleaning lady. We’d like to pretend that we have come a long way since then, but if you walked into one of those buildings today or looking around the industry – whether gaming or edtech – you have to wonder how much that’s true.

The reality then – and now even more so – is there are ultimately so many career possibilities. But when you don’t know that those opportunities exist, how can you aspire to them? When we only focus on coding, we’re showing kids just one window.

I have three kids and get asked a lot if I co-founded 7 Generation Games because of them. Sounds like a feel good story. But with two parents who have private university degrees and professional jobs, my kids will have so many options. If you ask my oldest daughter what people who work in big buildings or say video game studios do, she could rattle off a list. Ask her if she thinks she could make games some day, she will give you that middle school duh look. If you’ve got one, you know what I mean. Her mother and her grandmother – my co-founder – both work in the industry. If we two not-cool, old ladies can do it, it can’t be that hard.

However, we work almost entirely with Title I schools, many where 80-90 sometimes 100% of the kids live below the poverty line. When I ask how many of you like video games – 100% of hands shoot up. I ask how many of you think it would be cool to make video games? 100% of hands. How many of you think you could make video games? And often it’s 0. This hasn’t happened once or twice but dozens of times.

OK, what do people who make video games do? I ask. Well, they code, kids say- but not only do they code, but they’re like super computer geniuses. First of all, I am sure we can all attest not EVERYONE in this industry is a super computer genius. I’ve worked with a few people who I was amazed could even figure out how to turn a computer on.

And then I follow it up with, what else do people who make video games studios

do? I may get a random idea or two, but in the beginning it’s mostly blank

stares. However, as we walk through the design process, they come to see the

many parts – the people and therefore the possibilities – that go into creating

games.

I have a talk I give when presenting to kids where I correspond parts of creating games to body parts. Design is the heart. Design flows through everything you do. It is where the story starts.

I was working with a group of high school kids on a Dakota reservation in rural Minnesota last October to tell their story. We were brainstorming narrative – as I typically do in a game design workshop, I talked with the kids about this is your opportunity to be a part of creating a game that will portray your history and tribe. What do you wish people knew?

I think a lot about the 16-year-old girl, who when it was her turn, said, “I want people to know we are still here.” It wasn’t wistful, just factual.

That feeling of invisibility is recurring. When we released our first game, we got a call from a site that serves American Indian youth in Oakland, California. The tribe portrayed in our game wasn’t from this area, but the program director said “We want the game because our kids never see Native characters in anything.”

All kids deserve the opportunity to see themselves – both reflected in games, and as people who can make them.

This is important because let’s be honest the gaming industry is one of many that is failing when it comes to diversity. In the U.S., it’s 61% white, 4% Latino, 1% black, maybe a decimal point Indigenous, if we’re being generous – and overwhelmingly male.

I have had many people get defensive and ask me, “Are you saying that just because I’m [insert whatever demographic] I can only create games or storylines about people like me?”

Although, let’s be honest, based on the aforementioned industry makeup and data examining playable game protagonists – I’d argue that’s pretty much what’s already happening.

Couple that with the fact that the reply with the greatest number of respondents to the question “In the last year, to what extent has your studio focused on inclusion and diversity initiatives?” in GDC’s 2020 State of the Game Industry Report was “None at all.”

At the same time, you have Black and Latino players identifying as gamers at a higher rate than white users. What does it mean, especially to youth when the depictions of “people who look like them” in games can basically be broken into: athleticized, marginalized, sexualized (that has actually improved overall – so progress is possible) and villainized? Now, people always want to point out the exceptions to show it’s not an issue.

It’s like saying this isn’t a picture of a whole bunch of snowmen because there’s a panda bear in it. I know you’re all looking for the panda – who is right here. For the record, using animals or inanimate objects as characters for learning games does not circumvent needing to address inclusive representation.

Back to the question, “Am I saying that you have to be from a community to create a game around it?” My answer is “Authentic portrayals cannot come from Googling.”

If we lived in Utopian world, all tech companies’ teams would reflect society. All students would see themselves accurately and fully represented in the media they consume and curriculum they’re taught. But since 2020 so far reads like the backstory of a dystopian graphic novel, I think we can agree we don’t.

I’m not saying there aren’t talented people working on solutions – hopefully that includes many of you. But the gaming industry is not at the point where we have created environments that encourage diverse voices and foster diverse talent. EdTech as an industry is severely lacking there as well.

This is where engaging the community in design comes in. That can be hard because we as designers have an idea of what we want out games to be – but I also think one thing we always want out games to be is better.

At 7 Generation Games, we start with middle schoolers – who as a whole are the most creative yet brutally honest people on the planet.

Our company was initially founded to help close the middle school math gap in Indigenous communities. U.S. students as a whole are underperforming in math with Black, Latino and Indigenous youth faring among the worst. At the same time, data shows the value of culturally relevant curriculum – but when invited to analyze the National Indian Education Study, our team found the more time spent on culture, the worse kids did in other areas of assessment. This makes sense because ultimately the school day is a zero sum game, meaning if you increase time spent on one subject, it’s got to come from another subject – unless, we proposed, it doesn’t.

From there, 7 Generation Games was born – to create educational games that use cultural storylines to teach math in context. Because we had experience in the first communities we worked with, we somehow convinced them to replace math twice a week with our first functional – and I’m using the word functional generously – prototype. We were developing for tribal schools, and there is no quicker way to alienate an audience than to inaccurately portray their culture– so we built it hands-on with educators and elders on the reservation. We all played through it and thought, “Hey, this is pretty cool.”

So we showed up with what we thought was a super-awesome game, where you are saving your tribe from an epidemic – we’ve got this cool 3D world, there’s AI built in, learning modules if you get answers wrong – to save your village, you follow the arrows. Now, we put it in front of a fifth grader who sits down, sees the arrow signs and takes his character off running the opposite direction, until he falls off the edge of the virtual world. This happened with three consecutive kids at which point we said, we’ll be back tomorrow – and back to the hotel.

We return the next day, put the game back down in front of the same kids again take off running in the wrong direction, only to be met with newly installed barriers that redirected them to the path. We had expected to get an “aw, man reaction,” but it was as if their minds had been blown. They had led to this change. Their input and feedback made a difference.

I will never forget the teacher telling us the next day how she heard one of the boys boasting to his friends, “You know how when you go off the path, it tells you, you have to go back? That’s because of me.”

It was in that moment we started to see the transformative power integrating youth in real-world game design could have even in a messy buggy barely functioning MVP. My co-founder/mother talks about how when you give someone a finished product and ask, “What do you think?” you’re really asking for approval, not input. It’s too late to make meaningful changes. So we decided we couldn’t just build games for kids – we had to build games with them.

We spent the rest of the week and several visits over the next year working with the kids, determining what the game should look like and include, how we could integrate the math into the storyline. How we should have powwow music when you enter the village and hunt buffalo.

Now when I go to do design workshops five or six years later, kids will tell me, “My brother or my cousin MADE that game.”

When you work – or live in small towns – word travels fast. So before we had even finished Spirit Lake, we got a call from the next reservation over, asking when we were coming to build a game out with their kids. This is the point where I say thank you very much for the Department of Agriculture as lots of people thought building games to close the math gap for tribal communities was a great idea, but only USDA initially gave us money to make it – as well as another series for English-language learners – happen.

And kids have great ideas. Like creating a ribbon shirt activity where the ribbons – as virtual manipulatives – represent different fractions. There was a river and they wanted to swim in it – which evolved into a discussion about if you’re creating a character that swims you’ve got to account for 6 variables – head, body, arms, legs – that makes the programming complex.

“However, if you made it a canoe,” one girl pointed out, “that would be one variable.” Which is why you now canoe down the river. Well, part of the reason. I would be overstating if I said that we basically turned all of our design over to middle school students, and the reality is the final design doesn’t come just from one kid saying you should have a canoe but is a composite of several kids having several ideas that ultimately merged with our internal design into Canoe Dodge.

When we expanded into Latin America, we brought what we learned on the Spirit Lake reservation with us to Santiago, Chile as we developed Yaima y Manuel Rodriguez. And the first thing kids comment on when they play the game, before the intro video even stops, “This is in Chile.” You might think Manuel Rodriguez, one of Chile’s founding fathers- is what tips them off, but it’s not – it’s always the accent. From the opening scene, the narrator sounds like them.

We find that often kids who never see themselves reflected in anything don’t even truly realize the extent of that until they are exposed to something where they are. It is as if they are suddenly introduced to the idea that such games or curriculum not only could – but should – exist.

Whether it’s in rural South Dakota, the inner city of Los Angeles, the Caribbean beach of Trinidad or the Andes – when kids see characters that “look like them/sound like them/live like them” as well as when they see diverse characters that are so different from what they’re used to seeing – the question that it always leads into is “how do you make that?” Which leads us back to game design.

Now being this is Games for Change, this audience is far more likely to be working within the gaming industry or have some technical skills. But the vast majority of the world doesn’t.

Another key reason we specifically chose design – versus coding or hands-on game development — is design can be used as a low-tech framework, eliminating barriers that have long made the game industry feel out of reach – especially for kids in low resource communities, who often have neither access to high-end technology nor to adults with the skills to walk them through the process.

“We tend to compare our first drafts to other people’s finished products.” So I like to start game design workshops with this. After all, this is how every game starts. As nothing. A blank page and ideas in people’s heads. You’ve got that, right? I’ll ask kids. And they nod.

Then I show them this, which hangs framed in our offices – it was my co-founder’s, she’s a statistician, not an artist, map of what would become Fish Lake.

And I ask, could you do this? This is my mockup for that page, clearly I’m not an artist either. Middle schoolers – as incredibly willing critics – will resoundingly tell you, yes, they could definitely do better than mine. Can you do this? Which was a mockup for that. And by the end, we have demystified the process. It’s not some super exclusive career that’s inaccessible, but a series of steps that they’re more than capable of completing.

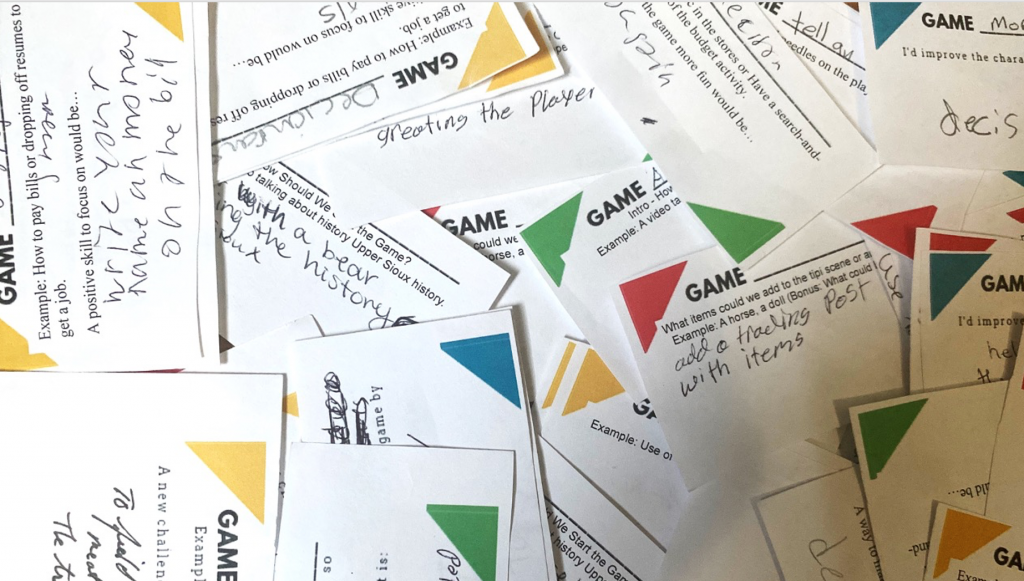

Now, I said I wasn’t going to have a quick fix – but I do have one turn-key activity we came across that was game-changing. These. Let me explain. When we started doing game design with youth, we would ask the same kind of things we would throw around in design meetings. What would you put in a game? Challenges. Gameplay. Narrative. Characters. Environments. We were generating ideas, but sometimes felt like a forced class discussion. Until we added these – literally some template cards, color-coded with examples and a couple of sentence stems – and suddenly, it was as if we unlocked a hidden level. We got, and I kid you not, after all, my co-founder is a statistician, so she likes to track this kind of stuff – and 80x increase in game design responses. These were like a super power-up for ideas.

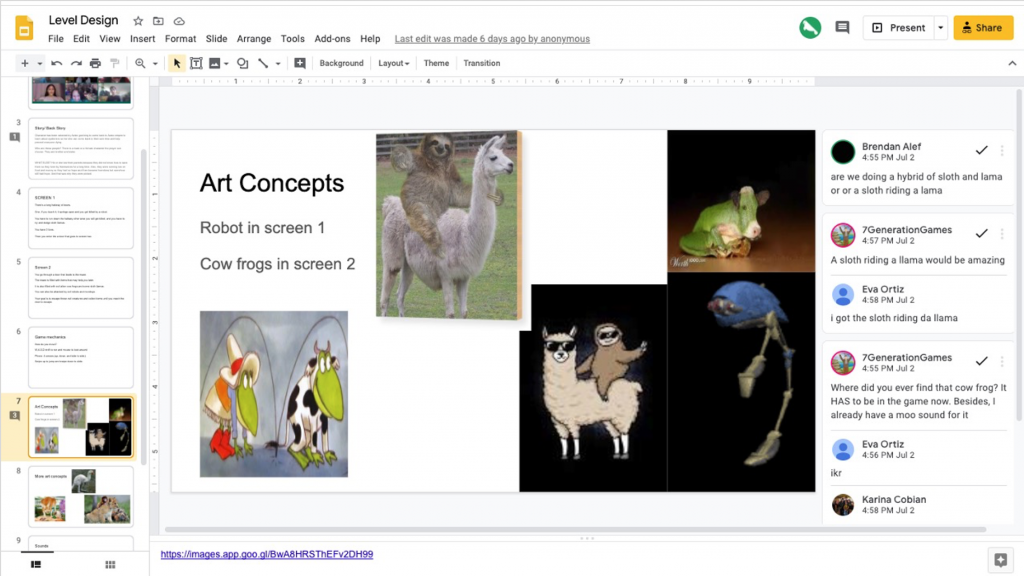

Not all ideas make the cut – we do historically accurate educational games, so the requests for zombies (a few years ago, everyone was obsessed with zombies – now it’s llamas), is a stretch. But then again, when you use culture and history as the storyline, maybe there is a way to kinda make it happen – which is how the Windigo found its way into Forgotten Trail, a game based not-only on the Ojibwe migration, but our first game set in the present day. Because even cooler than zombies is being able to create games that reinforce to kids, “You Are Here.”

We’re currently working on two game series – and this summer, COVID-19 forced things online. But that enabled us to run virtual game design workshops. Each session, every day for two weeks, we’ve brought together kids – and I say brought together, but really they bring themselves – during summer their break for no credit beyond a mention in the game credits. They’ve made messenger groups, so they can continue to talk about their project outside of the class time.

Across every U.S. time zone and from four continents, we’re able to reach kids from areas not renowned for their gaming industries – where we’re probably the only person who works in tech that many of them know. Two thirds have been girls – including Raine who joined us every day from the Philippines where it was 5:00 AM.

Earlier, I referenced Saint Expury’s quote from the Little Prince about what adults see when they look at houses. I think about that a lot when designing games with kids.

When you work with adults to design educational video games, they say things like, “The math needs to be Common Core aligned” and we need to integrate scaffolding and “The Aztec Empire would typically be covered in 6th grade.” All valid, but…

Then I look at the most recent session of game design kids who presented a six-level game with storyline, concept art, original sounds files, problem suggestions, customization ideas and ways we could adjust games for varying levels of difficulty.

When given the opportunity, game design presents kids who rarely have access to the process a chance to explore a world beyond their own. And it helps make better games.

Thank you.